Twice as many new-boat buyers are over 65 as are under 40 and that gives forecasters gray hairs

No matter how you dice it, the data is clear: Boat buyers are getting older at a rate that’s outpacing overall aging in America. And that’s not just new-boat buyers. Used-boat buyers also are aging, albeit not as quickly.

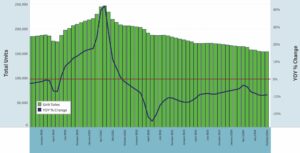

Since 1997, the age of the average new-boat buyer has increased from 45 to 53, says Jack Ellis, of Miami-based Info-Link, a company that tracks sales data for the boating industry. “It’s not like there was this sudden shift. It’s just a constant.” During the past 15 years, the percentage of new-boat buyers under 40 has shrunk by half — from a third to 16 percent, says Ellis.

In 2010 the median population age increased to a new high of 37.2 years, an increase of nearly 5.4 percent from 35.3 in 2000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Those numbers also include children, who obviously aren’t in the boat-buying market. Still, that is much less dramatic than the increase in the age of new-boat buyers during that period, which jumped 12.77 percent, from 46.2 years old to 52.1. (Age averages add the ages of all buyers and divide by the number of buyers. The median is the age at which half the people are younger and half are older.)

The brokerage numbers are better, but not by much. “We found that, on average, preowned boat buyers were roughly the same age as new-boat buyers back in 1997,” says Ellis. “Since then, preowned boat buyers have also gotten older, but not at the same rate as new-boat buyers. Today the average preowned boat buyer is about four years younger than the average new-boat buyer. This is consistent with the other research we have done that shows first-time boat buyers are younger than repeat boat buyers, which, of course, makes sense, and the fact that first-time buyers are more apt to buy preowned.”

The aging of boat buyers and the overall population correlate directly with the types of boats being sold, Ellis says. For example, the recovery in pontoons has outpaced most other segments. “The guy who bought his runabout or ski boat 15 years ago in his early 40s, now he’s in his early to mid-50s, and his kids have left home. A pontoon is perfect. So you can see some of this playing out. It’s a major concern of mine.”

Generational fluctuation

The aging baby boomers have made a ripe target for boatbuilders. It’s one of the largest generations in U.S. history, the group is reaching or already has reached retirement age and has the time to boat, and boomers more often have the means to afford a new boat. But Ellis cautions against ignoring the larger implications.

“The people who were buying boats 15 years ago are the same people buying boats today,” he says. “Today there are twice as many people over 65 buying boats than there are under 40. If this trend continues, the assumption is that it’s only a matter of time before our core market just gets too old to buy a boat. I know we keep wanting to stick our heads in the sand, but that’s scary.”

Part of the emphasis on the boomers can probably be chalked up to the fact that the generation following the massive group of boomers, generation X, is relatively small by comparison. Combine that with a prolonged economic downturn, and it makes sense that this group would be challenged to invest in a boat. But subsequent to the gen-Xers is generation Y, or the millennials, which is another huge group of people and one that some boatbuilders are already trying to reach.

Bryant Boats president John Dorton recently partnered with a design college to task a class of millennials who were students there to come up with the next generation of boats. The feedback was overwhelmingly clear, Dorton says: Their parents’ boat will just not do (see accompanying story).

But it’s difficult to market boats to an age demographic that is by and large still too young to buy a boat, says Thom Dammrich, president of the National Marine Manufacturers Association. “The oldest of the millennials are 35, tops,” Dammrich says. “When you consider that the prime age group for boat-buying and ownership is between 35 and 60, the millennials just haven’t quite reached that point yet. But the millennial generation is just as big as the boomers, so when they do reach that age we should be ready for that. I think if you look ahead, in the next 10 years you’ll have a lot of those millennials in that 35- to 45-year-old, boat-buying age range.”

Often people cite the rising price of boats as the reason it has been increasingly difficult to attract younger people. “I think affordability is one of the things we have to focus on,” says Paxson St. Clair, CEO of Cobalt Boats. “It’s a factor for all of us. We tried to produce a few new models that are lower in price point. And we are high-end, no question.”

Jason Constantine, the new 36-year-old president of Back Cove Yachts, thinks limited disposable income, regardless of income level, is a hindrance to the boating lifestyle. “A small bass boat with a 30-gallon tank costs $100 to go out on for the weekend, and that’s a significant cost when some are figuring out their monthly budget. Larger boats, like Back Coves, are efficient to run, but when you’re talking about slip fees, launching, storage and maintenance, it’s not an insignificant amount of money.”

Constantine says he likes the fact that some of the larger builders are trying to offer boat packages that include engines and trailers for less than $20,000. Notable in this group is the Bayliner Element, which targets younger buyers, as well as those in other age demographics with limited discretionary money, says Brad Anderson, vice president of marketing and planning for Brunswick’s fiberglass recreational group, which includes Bayliner, Meridian and Sea Ray. “If cost is prohibiting some users, regardless of demographic, the Bayliner Element’s a great example of giving customers an option for $13,999 or less, fully outfitted, and $150-per-month payments or less with zero down. It allows people to participate in that boating lifestyle at a very economical price,” says Anderson.

“Why do you think you’re seeing so many people get into the jetboat business?” Dammrich says. “They’re smaller, less expensive, and I think they probably appeal to that millennial generation. In general, less expensive boats are always going to be a key to bringing younger people into boating. I think it’s too soon to tell if it’s working, since most of them are still pretty new, and again, that millennial generation is still a couple of years away from being in a buying position. But I think the moves you’re seeing today are anticipating where the market is going.”

Trends shifting

The increasing age of buyers could be affecting the uneven recovery among various segments. “The aging of the boater has affected every segment of the industry, but some more so than others,” Ellis says.

“Nobody wants to be out there in the super-cheapest, smallest boat, and quite frankly I think that’s one of the reasons the pontoon business has done pretty dang well over the last few years,” St. Clair says. “Granted, they’ve done a great job in pontoons with features and performance.” But on top of that, a family such as his — St. Clair has four kids — can get out on the water in a pontoon with their friends while spending $30,000 on the boat. “In other types of boats it’s going to be a pretty small boat with a pretty small engine and not nearly the comfortable amount of room a pontoon affords for that price.”

Anderson says that historically pontoons have resonated well with boomers. “At the same time, you have a lot of younger people moving into the category,” he says, especially with the advent of higher horsepower engines on those boats and innovations such as triple tubes. Given price points that range from $18,000 to $100,000 and the large range of performance characteristics, their appeal stretches across age groups, Anderson says.

Many Back Cove buyers are boomers shifting away from sail because they no longer want to handle a sailboat, Constantine says. “They’re drawn to the Down East design because it’s classic and more like what they’re used to,” he says. The rest tend to be boomers who have owned boats for a decade-plus.

“When we watch our customers go through our product lines, they might come in at a Back Cove 30 and then maybe trade up to a 37, or then move into Sabres at 40 or 50 feet,” says Constantine. “As kids grow up and leave home and the parents are home alone again, they don’t need a great big boat, and they’re trading back down into something smaller, like a Back Cove 30.”

For builders such as Back Cove, the hope with those lower-priced, entry-level boats is that more people become interested in and excited about boating and eventually trade up, Constantine says, and eventually begin to look at Back Coves and sister company Sabre Yachts. “If you’re going to bring in new folks, you’re probably not going to bring them in at 30- to 50-foot cruising yachts,” he says. “They’re going to get in with something small and manageable.”

Although Cobalt also doesn’t specifically target that buyer, St. Clair says those new value boats are great for the builder in the long run. “We want people to get into those boats because we hope that if they continue to move into different product categories, we’ll have a shot at them later,” he says. “It’s better for someone to get into brand X and into the boating lifestyle than joining a country club and teaching the kids to play golf.”

Demands on time

St. Clair touches on another issue that historically has challenged the boating industry: Boating is not only expensive, but it also has to compete with all of the other recreational activities available. That may be even more challenging today, given that many families have two parents working full time and a slew of kids’ activities. “I think that is a concern,” St. Clair says. “I look at what I did as a kid versus what my kids are doing, and it’s night and day. The activities and the things that everybody’s involved in, it’s just crazy. As a result, you don’t have that time to get out on the water.”

In addition, the average workweek has increased, compared with 20 years ago, Constantine says. “If you go back to the ’50s, it was 40 hours, and you left work and forgot about it until the next day,” he says. “We’re so much more connected now. … If people worked a 40-hour week on average in the past, is it 55 now?”

Constantine is not alone. On the days they worked, 36 percent of employed people age 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher did some work at home, according to a Bureau of Labor Statistics time-use survey. A Good Technology survey from 2012 shows the average American puts in more than a month and a half of overtime a year just by answering calls and emails at home. It also found that more than 80 percent of people continue working after leaving the office — an average of seven extra hours a week. That’s a total of close to 30 hours a month or 365 extra hours every year.

The long-held marine industry adage has been that boaters stay in boating. “I believe that quite often those boomers represent access to that younger generation,” St. Clair says. “Often that generation has other priorities and new homes, so they use up that disposable income. Often the way to get kids and grandkids into boating is through that boomer group.”

Dammrich says people who grew up boating will stay in it if they make it a priority. “Time and money have always been a constraint,” he says. “There are studies that go back decades to show that. But when the kids are grown, are they going to sit around talking about all the great times they had in the minivan going to soccer? No, they’re going to talk about the times they spent on the boat. And let’s face it — boat ownership is not for everybody. But for parents who want to spend quality time with kids there’s no better way to spend quality time with a teenaged kid than on a boat.”

Constantine sees it differently. “My parents had a small sailboat on Lake Champlain,” he says. “It was fantastic, and that certainly sparked my interest in boating. But I’ve got two young children, and there just seems to be a lack of time. I would love to have a boat, but the reality is that I don’t have the time to spend on upkeep. The time we do get out is fantastic. I think a piece of the challenge is we’ve got more households with two working parents, so you work all week and then on weekends we’ve got housework to do and grocery shopping, and all these other not-fun things. Then it’s back to work.”

The time and financial commitment is at a tipping point for Constantine’s family, who lives in Maine, where Back Cove is based and the boating season is about three months long. “I’d be curious to know how many children of avid lifelong boaters are not getting into boating,” he says. “And I don’t know the answer to that question.”

Trudy Almquist, who is CFO at Partners+simons, a Massachusetts-based marketing firm, grew up boating at her family’s vacation cottage on Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire but does not own a boat now. “We grew up sailing, water skiing and boating all over the lake,” Almquist says, which made for “wonderful family memories.”

When she was married, she and her husband had a home in a lake community and a MasterCraft, which they loved. But the “water ski season got squeezed a bit when my stepson was in high school sports,” she says. “So there’s another reason — kids’ sports. There are a lot more organized activities for younger kids than when I was a kid. And now I’m raising a toddler as a single mom, so both time and money are very limited. By the time I have the time and money, [my daughter] will be too busy with various sports and activities.”

Almquist calls herself a demographic anomaly. “I raised a teenager in my 30s and [am now raising] a toddler in my 40s,” she says. But her situation is increasingly common as more families become less traditional.

Space

The fact that people are living longer is also affecting the boating industry, says Bentley Collins, vice president of marketing and sales at Sabre Yachts. “My yacht club is limited to 250 members,” he says. “We did a census to see how old members were, and it turns out our members are really old. We can’t create openings for new people to come in. Every yacht club is dealing with the same issues of having an aging population. We’re living too long. There are no new clubs being formed. No new marinas are being built. So if you have a limited number of chairs in the game of musical chairs, we’re not going to increase the boating population unless we do it in another way, which is through trailerable and dry stackable boats.”

The aging factor is even more dramatic in the 30-foot and above segments, says Collins. Collins’ 36-foot boat and dinghy require a 42-foot slip that costs $4,400 a year. “Add insurance to that, winter storage and before much longer I’ve got a pretty big bill to own and operate a boat for a year,” he says. “It takes someone who’s old enough to have deep pockets, and I think it’s only natural that the audience is going to age.”

The boomers

Baby boomers have “short-term” or “immediate” potential for boatbuilders, depending on whom you ask. The population aged 45 to 64 grew at a rate of 31.5 percent, Census Bureau data showed. The population aged 65 and over also grew at a faster rate, 15.1 percent, than the population under age 45.

“For some of the builders this is not bad news, at least for the short run,” Info-Link’s Ellis says. “For the builders selling higher-end or bigger boats, there are more people reaching the age where they can pay for those types of boats. But if you’re looking at the long term, not many people are coming in on the back side. It’s common in any business to look at the next five years instead of the next 15 years. And how do you affect it? You can’t as a single company say, OK, we’ve got the solution to get younger people into boating. It’s got to be done as an industry.”

Says Cobalt’s St. Clair: “I feel this boomer generation, this group, is the right age for boating. It’s ready, right here, right now. It’s a group that can afford to boat, has time to boat, and so let’s take advantage of it. To a certain degree we’ve had a pretty darn good year, and I think that’s part of our success. I feel sometimes we take the approach to go out and find these other opportunities, which are sometimes a real stretch because the buyers are few and far between, when we have this incredible group of people that are kind of target-rich.”

Ellis agrees that the boomers are a great boat buyer for today but maintains that the industry should stay focused on bringing more boaters in from subsequent generations. “That’s why I think one of the NMMA’s initiatives to attract more younger boaters is so critical. We can’t afford to ignore this much longer.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2013 issue.