Editor’s note: This is where things stood in marine finance in early October. The banking environment, however, was changing on almost a daily basis, and the situation may have changed in the interim.

As financial institutions drop out of marine industry finance, dealers say credit has tightened and they worry not only that interest rates will rise, but in some cases fear they will be forced out of business.

KeyBank, which announced in late September it would leave both retail and wholesale marine finance, is the most recent example in a long line of top-15 financial institutions that have scaled back or abandoned marine lending altogether.

“Certainly it isn’t good news anytime any of the lenders pull out, and it has created a whole additional level of fear, and we’re all dealing with that right now,” says Fred Pace, managing partner of Legendary Marine, which has four locations in Florida.

Now, many say, it takes a bulletproof customer to secure financing: a stronger credit score than before, money in the bank, a debt-to-income ratio no higher than 40 to 50 percent, a down payment between 10 and 20 percent, higher income and more documentation.

The credit score needed for acceptance seems to vary from customer to customer, typically falling somewhere between 680 and 720.

Rejections mount

Pete Messier, owner of Boat World in Rhode Island, says he’s looking at his options for the future in light of the credit crunch and dip in sales.

“Good credit isn’t good enough; it’s got to be excellent credit,” Messier says.

About 30 percent of loans that would have gone through six months ago are now getting turned down, Messier estimates, and Boat World is feeling pressure from the tightening on the retail side and dwindling competition on the wholesale side.

“We’re getting squeezed on every side,” says Messier. “It really makes it next to impossible to do business. They’re getting strict; they don’t want to loan as much money, and they don’t want to loan on anything over 10 years old.”

About half the applications are getting turned down at Spring Brook Marina in Seneca, Ill., that would have been approved six months ago, says owner Jim Thorpe. One potential buyer wanted to borrow $1.2 million, had a credit score above 800 and had 15 percent to put down.

“Three different banks turned him down, so we lost the deal,” Thorpe says.

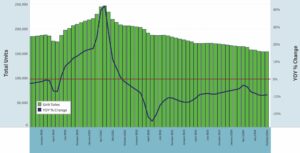

It is especially frustrating when sales already are sliding into double-digit downturns nationwide. Numbers from Fort Lauderdale-based Info-Link, which tracks new boat registrations nationwide, show a 14 percent drop in sales from the second quarter of 2007 to the second quarter of 2008.

Thorpe says one Florida dealer who sells smaller boats than those in Spring Brook’s 30-foot to 85-foot range, told him out of 30 boats he sold in September, he could only get two financed.

Lower-quality buyers

Larry Morris, who works in sales at Galey’s Marine in Bakersfield, Calif., says not only are bank standards getting more stringent, but the quality of applicant is sliding.

“In a slower market, you lose your upper-quality buyer,” Morris says.

Previously, about 70 percent of applications were approved and 30 percent turned down. Now 70 percent are turned down, “mostly because you are getting lower-quality buyers,” says Morris, who has worked at the 70-year-old dealership since 1964.

Rob Soucy, who co-owns Port Harbor Marine in South Portland, Maine, says what is being approved hasn’t changed, but he thinks the process has dramatically slowed, and that costs him sales.

“What we’re finding in these more challenging times is, any hiccup or speed bump in the process causes people to stop and think,” Soucy says. “It causes people to change their minds [because] they get buyer’s remorse before they buy the boat. Again, it’s not helping.”

SunTrust Bank wants a down payment of between 15 and 20 percent, says Don Parkhurst, vice president of marine lending there. The average credit score is about 690, and the applicant is reviewed for liquidity and net worth, Parkhurst says.

“Where it’s had the impact is on the marginal customer,” Parkhurst says. “Some of the players that got out were specializing in that customer.”

A big player gone

Some industry players get emotional when discussing KeyBank’s decision to lop off its 50-year-old recreational lending business. Cleveland-based Key is one of several lenders to recently pull out of marine lending. This summer, Citizens Bank and Wachovia pulled out of marine finance, and GE Money quit retail marine lending.

“When you’re looking at it from big-picture strategic perspectives, there are a lot of big players leaving and not a lot of big players coming in,” Parkhurst says. “Net-net, the industry has had a dramatic loss of lenders.”

Key said it would stop accepting retail applications Oct. 27, and the last day for funding applications will be Nov. 14, according to Grant Skeens, president and CEO of Key Recreation Lending. The bank is working to transition dealers to other sources of floorplan funding over the next three to four months, Skeens says.

“It was a very difficult decision,” Skeens says. “Like any business, in this case Key Bank takes a step back and looks at where it wants to deploy capital.

“Certainly if you look at the prospects for the [marine] industry over the next 12 to 18 months, they aren’t very rosy,” Skeens adds. “I would tell you margins in retail continue to be thin for lenders.”

Skeens says Key is working as hard as possible to place all the dealers in its network with other lenders, but that its time in the industry will be finite either way.

“We’re going to do our best to transition people to another lender,” Skeens says. “This is Week 2 into this process. It’s really tough to know every single scenario that might or might not happen.”

‘A scary thing’

Many in the industry are disappointed at Key’s departure.

“When we lose big people like KeyBank or GE, that’s kind of a scary thing,” says Phil Keeter, president of the Marine Retailers Association of America. “I understand those big corporations have a fiduciary responsibility to stockholders and have to make certain profits, but that still devastates our industry.”

Dealers who used KeyBank for floorplan finance will be left scrambling to find another source, Keeter says. While dealers often use several sources for retail loans, many often use only one source for floorplan financing.

“Dealers have had two or three tough years, and they’re light on liquidity and here the financier pulls out from underneath them. It’s not very pretty,” Keeter says.

Jim Coburn, president of the National Marine Bankers Association and head of marine lending for Flagstar Bank, says others will eventually step up.

“As an industry marine finance veteran, I am disappointed in Key’s decision to exit recreation finance,” Coburn said in an e-mail. “I also understand the decision, amidst current uncertainty in the U.S. financial markets and their need to bolster and preserve capital. As a marine lender, I see opportunities as a result of these exits for banks and financial institutions.”

A boost from Buffett

Experts estimate KeyBank had between $1 billion and $2 billion invested in marine wholesale.

“From where we sit, we don’t want to get into size of portfolio,” Skeens says. “We were a significant player in the business. We were larger in retail than in commercial lending, but certainly a big player.”

GE Distribution Finance probably accounts for three-quarters of all floorplan financing, with more than $3 billion invested.

General Electric Co. announced Oct. 1 it would sell $3 billion in perpetual preferred stock to Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Inc., giving some in the industry hope that its finance subsidiary won’t drop out of marine. Buffett is guaranteed an annual 10 percent return on the stock for the next decade.

“That’s a sign of the times we’re in,” says Parkhurst of SunTrust — another bank in which Buffett owns stock. “If they’d had a better choice, they would have taken it.”

Norm Schultz, the former head of the Lake Erie Marine Trades Association, thinks the catastrophe is the result of banks changing a century-old banking formula — that is, making money on fees instead of making money on loans to qualified borrowers.

“We’re going to pay more for our money, at least in the short run,” Schultz says, anticipating rising interest rates. “That will be a product of the mess we’re in now. Probably more important is that we get access to wholesale dollars for dealers and retail for customers.”

There is credit available, says Coburn, but it is tighter because guidelines have returned to where they were about 15 years ago. Rates are beginning to rise in retail financing, and there are fewer national marine lenders in the game.

Floorplan finance

Port Harbor Marine uses KeyBank for wholesale financing, says Soucy. The 40-year-old dealership was bought by Soucy’s parents in 1974, and was taken over by Soucy and his two brothers several years ago.

“Having used Key for both the retail side and the wholesale side, it certainly was a blow to us, but one I’m sure we’ll recover from,” Soucy says.

Now Soucy is looking to expand the small line Port Harbor Marine financed through GE Money, as well as entertain other finance sources.

Port Harbor has not seen the economic slide that others are facing. In 2007, the company had a record year in its top and bottom lines, Soucy says. This September, business was only about 10 percent off, and Soucy anticipates the Maine dealership will finish out the year down 5 to 10 percent.

“I view it as, someone’s going to be glad to have us in their portfolio,” Soucy says. “If I were a struggling boat dealership, I would probably be more concerned about KeyBank pulling out. But most of Key’s dealers were the A and B dealers.”

Soucy is disappointed because he had enjoyed a long relationship with Key, and he felt the people he dealt with understood and cared about the marine industry. Now, Port Harbor Marine’s finance employees will have to forge new relationships at other banks.

“I don’t want to discount the fact that there’s a lot of concern,” Soucy says. “It’s not good for the industry. We would rather have more banks, for not only wholesale but for retail, too.”

‘Heartbreak’ at Key

Soucy says he has other dealer friends who financed through Key, but that he doesn’t know how the move will affect them.

One issue discussed among dealers was whether a new floorplan financier would take existing or aged inventory, Soucy says. Some dealers he had spoken to said banks they were in contact with were not willing to buy out their existing floor plan lines, creating a lot of concern among dealers looking for lenders.

“It’s so fresh, I don’t know,” Soucy says. “The ones I talk to didn’t seem like they were panicking. They were less concerned with being able to find a wholesale source; they were more concerned that when they found that source, was it going to be as nice a package as with Key with as favorable a rate? If there are fewer banks in the business, are they going to have a position of strength to say, ‘This is your rate and if you don’t like it, where are you going to go?’ ”

Skeens says Key will miss the marine customers as well.

“That’s the heartbreaking part of this whole thing, is the people,” Skeens says. “People internally and people you’ve established relationships [with] after years and years of working with them.”

Not even competing banks seem happy about the pullout, Soucy says.

Multiple sources

Morris remembers a time when Galey’s Marine in California lost its sole source of floorplan finance when its local Crocker Bank was sold and pulled out of the marine industry altogether.

“It devastated us,” Morris recalls. “We lost hundreds of thousands of dollars because we didn’t have a backup. From that point on, we’ve always made sure we had more than one source. We don’t give all of our volume to anybody.”

Owners of Dry Dock Marine Center in North Angola, Ind., also had to find another source of floorplan financing in the mid-1990s when their bank scaled back, says Cory Archbold, who now runs the business his dad bought in 1987 with his brother.

“The rule of thumb that we use since then — and the banks typically don’t like it because they want 100 percent of your business — is you always have more than one lender for your floorplan,” Archbold says.

Now Dry Dock uses GE Distribution Finance and Textron for wholesale and local banks for retail. That’s because local branches want Dry Dock’s exclusive floorplan business, and, since the incident in the mid-1990s that had them scrambling to find alternative sources, the dealership refuses.

Most of the dealers Soucy talks to in his Spader 20 group and as a board member at the Marine Retailers Association of America are most concerned about retail financing, which has seen more banks drop out and already experienced some rising rates.

“I keep hearing, ‘We sold X amount of boats and can only get two financed,’ “ says Soucy. “That one seems to be the more pressing issue for the majority of boat dealers.”

Dry Dock Marine does most of its retail financing through regional branches, like Star Financial, Archbold says. In his experience, local banks are still approving some zero-down loans and have more competitive rates. Others, like Morris in California, say local branches have traditionally been more cautious than national lenders.

Outsourcing

Theoretically, even those dealers with multiple sources could be up a creek if all of them happen to pull out, says Joe Lewis of Mount Dora Boating Center outside of Orlando, Fla.

That’s one reason he uses Priority One, a finance and insurance outsource company. That means the dealers looking for financing submit applications to Priority One, and the company shops around for a lender.

With its volume, Priority One has more leverage than a dealer trying to get one or two loans approved, says president Lisa Gladstone.

Priority One, which was recently purchased by a subsidiary of Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, had been privately owned since its founding in 1989.

“We only get paid if the dealer makes the delivery on the boat,” says Gladstone. “We only take a commission on extra profit that we generate.”

Lewis says he has been thrilled with his Priority One experience.

“I don’t have to worry about it; it’s not my problem,” Lewis says. “It’s going to be Priority One’s problem. It’s going to make their job more difficult.”

Often Priority One can get more favorable rates than a local credit union can give, Gladstone says. Approval ratios have increased from September 2007 to September 2008, she says.

Banking on the bailout

Parkhurst expects the much talked-about $700 billion bailout put together by the Bush administration and congressional leaders and enacted by the Senate and House, will help the situation.

“I think this is sort of the beginning of the end of the bad stuff since Congress acted,” Parkhurst says. “A lot of institutions that were in trouble have been taken down and married with bigger, more solid institutions.”

“We’re in place to start healing things,” Parkhurst added. “There’s still more to do, and there’s still going to be a recession and it’s going to go on for a while, but the problems in the banking industry are being dealt with and we’re moving forward.”

This article originally appeared in the November 2008 issue.