Listening to President Biden’s environmental orders cutting off the Keystone pipeline, ending fracking and attacking coal mining, all in the name of climate improvement, ignores the current and more pressing problem of harmful algae blooms throughout the nation’s waterways. It’s time to address it nationally with some serious funding.

Last week I went to use my boat at the Loggerhead Marina in St. Petersburg, Fla. It was an ugly scene. Normally clear, the water was a foul reddish-brown I’d never seen there. I asked the crew what was happening. A return of red tide? An early-season algae bloom? No one knew for sure, but it didn’t make boating very desirable.

It also triggered my recognition that we have a water crisis in this country that must be seriously addressed. When 150 public water systems in 33 states report harmful algae blooms at intakes in reservoirs and other water sources, when cities such as Toledo warn their citizens not to drink the water, when boating businesses can document a negative impact on revenues — you think there may be a serious problem?

Sadly, while algae in the water are natural, this explosion of blooms nationwide is largely manmade, and neither the federal government nor states are effectively acknowledging the crisis and cracking down on the contributors.

It’s been more than 12 years since a task force was convened in Ohio to figure out how to tackle the annual invasion of the green goop in western Lake Erie. Since 2011, the state has spent more than $3 billion to upgrade sewage and drinking water plants, but Ohio’s voluntary nutrient-reduction strategy has bombed.

The real trigger for blooms is agricultural runoff from farming operations in northwest Ohio and southeast Michigan, especially farms that cultivate corn, which is a high-demand fertilizer crop being grown for ethanol production. Indeed, the Ohio EPA admits that nutrient runoff from farms is the cause of a whopping 90 percent of the lake’s toxic algae. So one would assume it mandates serious action. Guess again.

“Everything we’ve done so far, trying to reach these reductions voluntarily, has had no impact,” said Jeff Reutter, a longtime Lake Erie researcher now retired from Ohio State University. “The voluntary approach has been, I guess you’d say, a total failure.”

Lake Erie is a microcosm of human use and abuse of the Great Lakes, according to a 516-page report drawn from the work of more than 40 Great Lakes science and policy groups. Meanwhile, in Florida, harmful algae blooms are seriously fouling such waterways as the Caloosahatchee River, which flows west from Lake Okeechobee carrying nitrogen and phosphorus-laden waters and triggering blooms in popular boating and fishing waters along the state’s southwest coast and Gulf of Mexico. But that’s just the start.

Florida’s east coast also gets slammed. Lake Okeechobee waters with high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus are similarly diverted east through the St. Lucie Canal into Indian River Lagoon and surrounding waterways. It also causes salinity levels to drop rapidly, killing many fish species in that estuary.

Where does the nitrogen-phosphorus cocktail come from? Like in Ohio, it comes from fertilizer, mostly from massive sugarcane cooperatives covering 70,000 acres in the Everglades Agricultural Area. Cooperative members produce more than 350,000 tons annually. All the fields are surrounded by canals that feed into Lake Okeechobee, and so it goes.

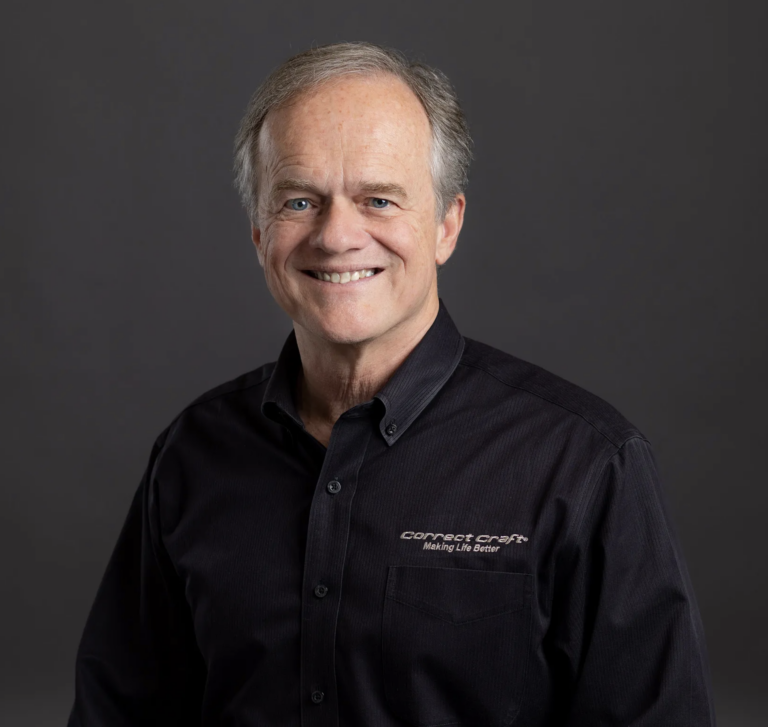

The impact of blooms on the retail boating industry isn’t well-known. However, the Southwest Florida Marine Industries Association is taking action by co-funding with the South Florida Water Management District, the first such impact study in the marine industry.

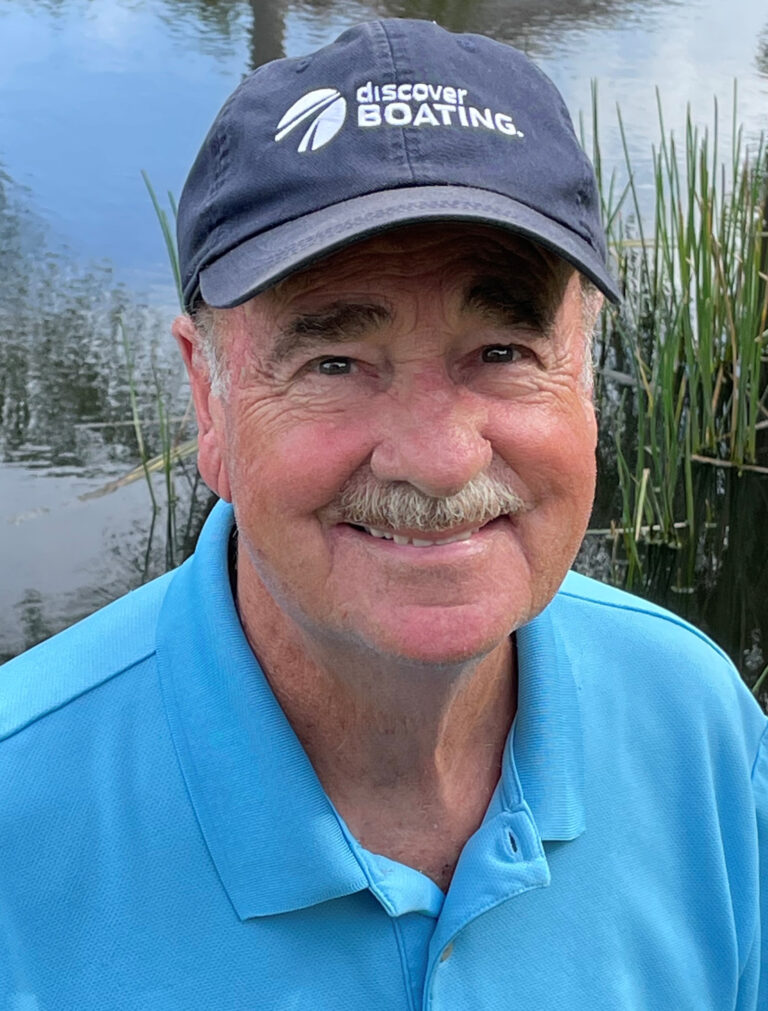

“We believe the algae blooms keep our retailers and marinas from seeing all the growth they could if the public was not turned off to boating because of the algae problems,” said John Good, SWFMIA executive director. “But we must quantify it economically to leverage law makers and regulators to take more positive actions. While Covid has slowed our study, we expect it to be completed soon.”

Meanwhile, states could set legally enforceable limits on the amount of fertilizers and nutrients permitted on applicable farmlands. In fact, the federal and state governments have the Clean Water Act as the undeniable basis for taking such actions. But when it comes to harmful algae blooms, responsible federal and state agencies remind us of the story of the tourist and the park ranger standing on the rim of the Grand Canyon.

Ranger: “You know, it took 3 million years to create this canyon”

Tourist: “Government job?”